April 1980 found the writer of the lead story in the Doctor Who Appreciation Society’s Celestial Toyroom newsletter (probably its editor, Chris Dunk) mourning the loss of an ‘unfinished classic’. This wasn’t Shada, whose production at BBC Television Centre had stalled a few months before, but David Whitaker’s return to novelizing Doctor Who stories. A few months before, it had been confirmed that David Whitaker would be writing Doctor Who and the Enemy of the World for the Target range of Doctor Who novelizations, his first commission directly for the Target series and his first novelization since Doctor Who and the Crusaders for Frederick Muller in 1966. However, on 4 February 1980 David Whitaker had died in Hammersmith Hospital. In the February 1980 edition the DWAS’s fan fiction zine editor, John Peel, could be found looking forward to ‘David Whitaker’s new books’. What might Peel have been referring to specifically, and what might a Whitaker novelization of The Enemy of the World have looked like?

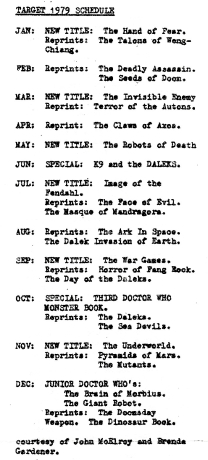

Celestial Toyroom for January 1979 printed the Target Doctor Who schedule for 1979, supplied by Target editor Brenda Gardner through John McElroy. McElroy then ran the DWAS’s overseas department and supplied Target titles to the society’s overseas members. The schedule as printed was largely that maintained during the year, with some obvious changes, but for a brief period there was a more drastic alteration which might indicate the titles Whitaker was expected to take on.

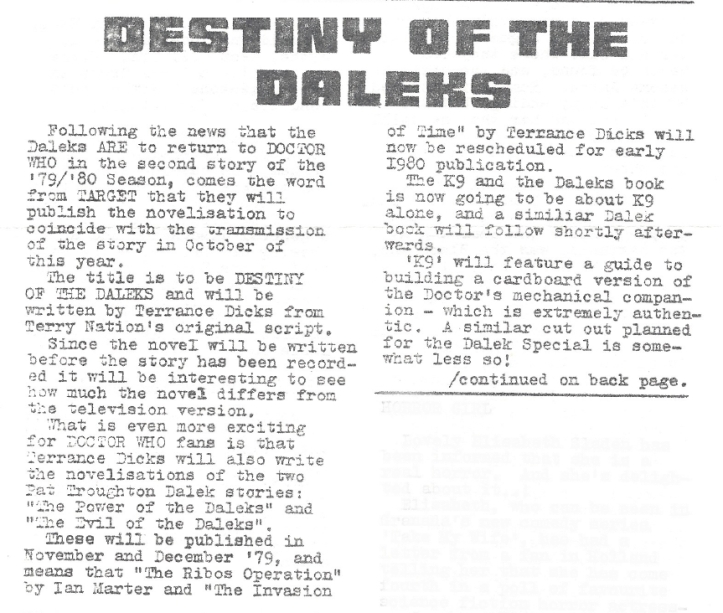

In April 1979 Celestial Toyroom announced that the first story of Season Seventeen would be Destiny of the Daleks, the first Dalek story for four years, written by the Daleks’ creator, Terry Nation. In addition, Target were changing their schedules to publish the novelization of the story within a few weeks of the series’ transmission. This was part of an audacious publishing initiative which saw two previously announced special publications, originally K9 and the Daleks and The Third Doctor Who Monster Book, change to focus on K9 and the Daleks respectively. (They would eventually appear as The Adventures of K9 and Other Mechanical Creatures and Terry Nation’s Dalek Special.)

Furthermore, Terrance Dicks was to follow Doctor Who and the Destiny of the Daleks with two more Dalek novelizations, Doctor Who and the Power of the Daleks and Doctor Who and the Evil of the Daleks. These were to be adapted from the two second Doctor Dalek stories, whose teleplays were both by David Whitaker rather than Terry Nation. Both presented tightly-drawn narratives in a limited number of settings and perhaps appealed more as candidates for adaptation than the remaining Terry Nation Dalek stories, the travelogues of The Chase and the unwieldy twelve- (or thirteen-) episode saga The Daleks’ Master Plan.

Everything then went quiet regarding the Troughton Dalek books. There was a report (also in the April number) that future Target titles would include The Keys of Marinus and The Monster of Peladon, both to be written by Terrance Dicks. In September a new schedule was published in Celestial Toyroom, missing both the Troughton Dalek titles.

Behind-the-scenes news then took over as the Howard & Wyndham group reviewed its publishing operations and decided that its children’s list warranted pruning. Brenda Gardner, the children’s editor, and her team were all made redundant and ‘the Target Books Department’ (which also included Longbow, W.H. Allen’s hardback children’s imprint), closed.

Target had been launched by Universal-Tandem Publishing in 1973. It functioned largely as a reprint list, combining paperbacks of titles originally published in hardback by other publishers with some paperback originals. Universal-Tandem had been bought by Howard & Wyndham in 1975 (edit though it appears that it was formally Howard & Wyndham’s subsidiary W.H. Allen which made the purchase – see The Bookseller 12 April 1975), was first renamed Tandem Publishing, and then in 1976 merged with the paperback list of Howard & Wyndham’s existing publishing house W.H. Allen to become Wyndham Publications. The Wyndham name seemed like an optional extra, as from November 1977 the Doctor Who paperbacks were attributed to ‘the Paperback Division of W.H. Allen & Co Ltd’, but the Wyndham logo remained on the back of the books and correspondents to the editorial address received letters with the Wyndham letterhead at least into 1978. From the publication of Doctor Who and the Masque of Mandragora in December 1977, the hardback editions of the books, hitherto issued under Allan Wingate, which had been used by Tandem as an imprint for hardback editions of paperback originals mainly marketed at libraries, bore a ‘Longbow/W.H. Allen’ imprint on the spine and were described as Longbow books, published by W.H. Allen, on the title page. During this period, with Brenda Gardner as editor, W.H. Allen published several original works of children’s fiction and non-fiction in hardback which they could then paperback themselves if sufficiently successful, but this strategy ended with the arrival of Bob Tanner as head of Howard & Wyndham’s publishing interests and Gardner’s ensuing departure.

The closure of W.H. Allen’s children’s division was reported outside the publishing press, for example in the London Evening Standard. Celestial Toyroom’s story ‘Wyndham Trauma’ saw John McElroy warn that although ‘Wyndhams’ were likely to honour the fifteen months of commissions already agreed, there would be changes in the long term, and in the first instance there would be no more special publications following the two published in 1979. The Doctor Who series would be edited by someone from the adult fiction list for the foreseeable future.

The December issue included a report suggesting that prospects for the Target Doctor Who series might not be as bad as feared, as Philip Hinchcliffe and Ian Marter had agreed to write one more book each. (Hinchcliffe’s novel would turn out to be The Keys of Marinus, previously associated with Terrance Dicks.) There was also a teasing suggestion that Target were in talks with David Whitaker. This would have excited some of the loudest voices in fandom, who were disenchanted with televised Doctor Who as it stood in 1979 and for whom the 1960s stories existed at best as distant memories with little documentation to support them. This contrasted to the 1970s serials, the majority of which had been turned into books by 1979.

Unlike novelizers such as Malcolm Hulke (whose death in 1979 led the September 1979 Celestial Toyroom) and figures associated with the early years of Doctor Who such as Verity Lambert, Dennis Spooner, Donald Tosh, Gerry Davis and Innes Lloyd, who had all given interviews to fanzines by the end of 1979, David Whitaker’s views on Doctor Who had not been widely shared. This was partly because he had been resident in Australia for much of the 1970s. One fanzine editor who did establish a correspondence with him, Gary Hopkins of The Doctor Who Review, later wrote that Whitaker ‘took the view that, as a story-teller, it was part of his job to maintain the illusion… created by moving pictures on a screen. He was justifiably proud of Doctor Who, both as a fictitious character and as a TV programme, and guarded its secrets well.’ (Doctor Who Magazine 200, 9 June 1993, p 17). Nevertheless Whitaker did contribute a short reflection and short story to The Doctor Who Review, published in issue 4, February/March 1980.

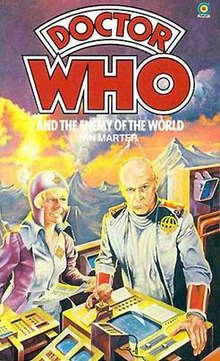

The January 1980 Celestial Toyroom reprinted a reassurance from W.H. Allen to the book trade that the Target list would continue, although the hardback children’s titles would not, and a mysterious statement that the Evil of the Daleks novelization had not been cancelled but the question remained as to who would write it. (The Power of the Daleks had been forgotten.) The news referred to by John Peel in February was confirmed by a report in Celestial Toyroom for March, that David Whitaker would novelize The Enemy of the World for publication in July 1980. The idea that Whitaker’s Dalek stories would follow would be a forgivable assumption. Unknown to most of those reading confirmation of David Whitaker’s return to Doctor Who in print, a future of David Whitaker books was not to be, for as mentioned above Whitaker died on 4 February 1980, while receiving treatment for cancer.

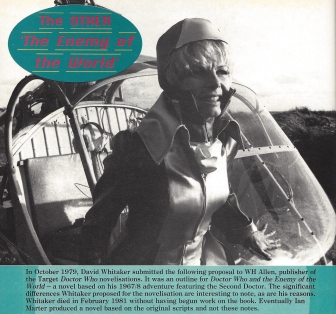

How, then, might David Whitaker’s treatment of The Enemy of the World appeared if he had lived? He has been quoted (in ‘a long David Whitaker interview from DWM’ – part one; part two – Paul Scoones writes that this was a feature in issue 98, March 1985, ‘Whitaker’s World of Doctor Who’, by Richard Marson) as having found writing Doctor Who and the Crusaders as more straightforward than Doctor Who in an Exciting Adventure with the Daleks as one script needed more restructuring than the other. He was joining a list where Terrance Dicks had mastered the art of recreating the viewer’s experience of watching the television series while often performing substantial but subtle surgery on a story. Whitaker’s surviving synopsis for Doctor Who and the Enemy of the World showed that he intended to continue his earlier practice of regarding stories as told in script form as necessarily very different from those told in novel form, even if the same broad argument was to be respected. The proposal appeared in Doctor Who Magazine 200 in 1993. Whitaker intended to remove Victoria entirely, fill in more details of the society of Earth in 2030 (advanced from the 2017 of the scripts, in keeping with the idea that the story was set fifty years into the future), and also show Salamander handed over to the people of the world for judgement rather than attempt escape in the TARDIS. It’s probable that he would have been encouraged to reconcile his novel with the broadcast serial, if only as far as the inclusion of Victoria. Nevertheless the proposal suggests that Whitaker novels would revisit the serials, overhaul them structurally and focus them thematically so as to better entertain the reader. Where Terrance Dicks sought to translate the viewing experience, which he did very well, David Whitaker instead envisaged literary Doctor Who as demanding more economy of character and sub-plot and more development of the main narrative if it was to succeed.

What, then, of the Dalek novelizations? After Doctor Who and the Destiny of the Daleks, no Dalek novels appeared until Doctor Who – The Chase in 1989. This was written by John Peel – the very columnist who had looked forward to future David Whitaker novelizations in Celestial Toyroom for February 1980. The history of W.H. Allen’s negotiations with Terry Nation is only known through fragments, but it seems possible, from what we know of the wider context, that had there been more Doctor Who books from David Whitaker, they would not have included his Dalek stories. Alwyn Turner’s Terry Nation The Man Who Invented the Daleks (2013) mentions that Nation and Whitaker supposedly had a quarrel, probably in late 1965, and Simon Guerrier in The Black Archive #11: The Evil of the Daleks (2017) presents reasons why Whitaker, as the man who commissioned and developed Terry Nation’s first two Dalek serials for Doctor Who, and much else, might have fallen out with Nation. Later in the 1980s, Eric Saward could not accept Nation’s agent’s financial demands concerning the proposed novelizations of Resurrection of the Daleks and Revelation of the Daleks, which remain unpublished (edit 18 November 2020: both appeared as BBC Books hardbacks in 2019, novelized by Eric Saward; paperbacks are expected to appear in March 2021 in BBC Books’s Second Target Collection). W.H. Allen’s renewed emphasis on certainty of profitability following its restructuring in 1979/80 might also have added some rigidity.

So, there is no certainty that Whitaker would have taken over the Power and Evil novelizations relinquished by Terrance Dicks. In the event, they appeared, in forms much longer than the standard Target format (described by Whitaker as 39,000 words), in 1993, written (like The Chase and the two-volume Daleks’ Master Plan) by John Peel.

Additional note, 18 November 2020: In addition to the in-text note regarding the publication of Eric Saward’s Dalek novelizations, I’ve also updated the date of the alleged quarrel between Terry Nation and David Whitaker to 1965. This is the date suggested by Alwyn Turner’s book. The correction was pointed out by Alan Stevens. Alan also alerted me to John Freeman’s citation of this article in discussion with Alan concerning the authorship of the comic strip The Daleks published between 1965 and 1967 in TV Century 21. This is appended to John’s article at Down the Tubes, covering the republication of the strip in a collected edition this month as a Doctor Who Magazine bookazine.